|

|

- Search

| J EMS Med > Volume 1(1); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objective

Uncontrolled emergency department (ED) visits lead to crowding and increase the time patients are in the ED. Following the 2015 Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak in Korea, EDs began to regulate visitors. The purpose of this study was to examine the results of regulating ED visits and to identify factors associated with increased ED visits.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional observational study using patient information recorded in a visitor’s book during the MERS outbreak from July 6 to July 26, 2015. The visitor’s book included the patient’s and visitor’s names, their relationship, and the day and time of the visit. The collected patient information included sex, age, mode of visit, length of stay in the ED, and disposition. The risk ratio and 95% confidence interval for each variable were calculated using Poisson regression. The primary outcome of this study was the number of visitors per patient according to their characteristics.

Results

Overall, 4,139 patients and 5,642 visitors were registered during the study period. More people visited during weekdays and office hours. The characteristics of patients that increased visitors per patient were when the mode of visit was a public ambulance and when the length of stay in the ED was longer than 12 hours.

Conclusion

During the study period, ED visits were strongly controlled by a government guidance, but there was still a significant number of visitors. If we do not restrict visitors, infection control in the ED will be difficult. It is urgent to develop policies and cultural improvement to control ED visits.

A large outbreak of the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) occurred in the Republic of Korea; it is the largest outbreak of MERS to occur outside the Arabian Peninsula since 2015 [1,2]. Within approximately 2 months, 9,793 persons were thought to have been exposed to MERS-coronavirus (CoV): 1,499 were quarantined and 8,294 were under active monitoring. One hundred eighty-six cases were confirmed, including 36 deaths [3,4].

After the MERS outbreak, the Republic of Korea–World Health Organization (WHO) Joint Mission announced the causes which exacerbated the spread of MERS-CoV in Korea: close and prolonged contact with MERS-CoV-infected patients in crowded tertiary care hospital emergency departments (EDs), multi-bed hospital rooms, and the custom of many visitors or family members staying with infected hospitalized patients [5,6]. The first MERS patient in Korea, who had traveled to the Middle East, was a visitor to local hospitals and infected another 36 persons, including patients admitted to the same hospital ward. The secondary patient remained in the ED of another tertiary-level hospital for another 3 days and spread MERS-CoV to 91 persons sharing the same space; this included patients, caregivers, medical providers, and visitors [4,7,8]. This ED saw countless patients from all over the country and drew a lot of visitors whose entrance was not controlled. This crowded environment brought people in close contact and helped spread the MERS infection [3,7]. Of the laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS, 38% occurred among people who were not healthcare providers or shared the same ward; they visited infected cases in hospitals such as family members, health care aides, and acquaintances who were patients [3]. Thus, visitors to the ED were a major vector for disease spread. Hence, some social consensus was required to control ED visitors.

During the outbreak, the Korean Centers for Disease Control (CDC) obligated hospitals to control the flow of people in the ED to manage the infection. They required hospitals to start recording the name, contact number, and visiting time of all ED visitors and accompanying persons [9]. After the official announcement from the CDC, we documented such information, which was entered by the visitors themselves, in a visitor’s book [9]. Furthermore, we instituted the rule that only one visitor per patient was allowed to enter the ED at a time; two or more visitors had to alternate. Before these policies were introduced, ED visitors could enter the facility without control.

This study aimed to share the experience of controlling ED visitors in a tertiary-level hospital during the MERS outbreak in Korea. We also identified the characteristics of patients that led to an increase in the number of ED visitors using the data collected in the visitor’s book.

This study was a cross-sectional observational study conducted from July 6 to July 26, 2015 in the ED of a tertiary-level hospital. This ED serves the local area and treats an average of 80,000 patients a year. It has 47 beds and operates three isolation wards. During the MERS outbreak, five security personnel were deployed to the ED. They enforced the rule that only one visitor per patient could enter the ED; and informed visitors that registering in the visitor’s book was mandatory.

We included all ED visitors, including public or private emergency medical service (EMS) ambulance staff and emergency medical technicians (EMT). Multiple visits by the same person within a day were considered as one visit. We excluded visitors with missing information, such as the visitor’s or patient’s name. Finally, visitors who refused to provide the personal information described above were excluded from the study.

We asked each visitor for consent before collecting personal information. Data collected included the date and time of the ED visit; the visitor’s name, age, and phone number; and the name of the patient to visit as well as their relationship. These were categorized into an immediate family members, other relatives, or acquaintances.

We collected the information of patients via a medical record review: demographics, mode of visit, day and time to visit, ED disposition, the length of stay in the ED. The Severance Institutional Review Board approved this study protocol (IRB No: 4-2016-0546).

We counted the daily number of ED visitors and patients and categorized the visitors’ characteristics: relationship to the patient (immediate family members vs. other relatives vs. acquaintances), day of the week (weekday vs. weekend), and time of the visit (office hours vs. non-office hours).

We also categorized the patients’ characteristics: age (adult vs. pediatric; where pediatric is defined as aged under 16-years-old), mode of visit (ambulatory vs. EMS; public EMS ambulance [119] vs. private EMS ambulance [129] vs. others [e.g., police]), ED disposition (discharge vs. admission to general ward [GW] vs. admission to intensive care unit [ICU]; transfer to other facilities vs. death); length of stay in the ED (more or less than 12 hours). We calculated the visitor-to-patient ratio based on the visitor and patient’s characteristics using multiple linear regression analysis. Each group was considered an independent variable and the dependent variable was the number of visitors per patient. We then analyzed whether there was a significant difference between the number of visitors within each subgroup.

The collected data were analyzed using SAS ver. 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). As the dependent variable, the number of visitors per patient was count data, it followed a Poisson distribution, not a normal distribution. Therefore, Poisson regression analysis was selected and performed using the SAS PROC GENMOD procedure. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The goodness of fit test was performed using the deviance obtained from each regression model to target the seven variables; models with a P<0.05 were considered suitable.

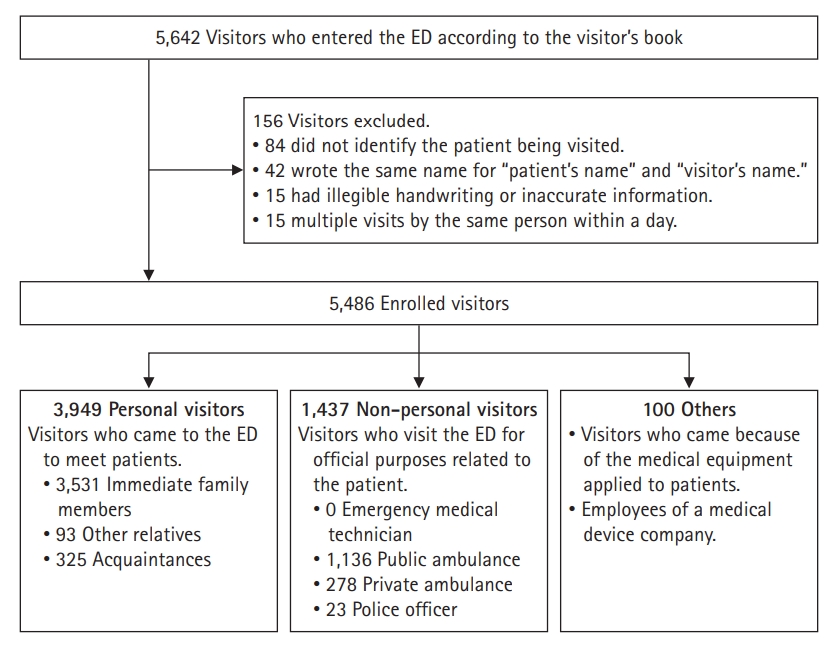

The outcome variable of our study is the number of visitors per patient (Table 1). From July 6 to July 26, 2015, 4,139 patients attended the ED. According to the visitor’s book, during the 21days, 5,642 visitors entered the ED. Of these, 42 wrote the same name for “patient’s name” and “visitor’s name”; 84 did not identify the patient being visited; 15 registered in the book several times a day; 15 were regarded as erroneous entries as the handwriting was illegible or the information inaccurate. All these entries (n=156) were excluded from the study, leaving 5,486 visitors for inclusion in the analysis (Fig. 1). Persons accompanying patients—such as direct family members, other relatives, or acquaintances—accounted for 3,949 of visitors (72%), while public or private EMS ambulance staff accounted for 1,414 (25.7%). Most accompanying persons (n=3,531 [89.4%]) were direct family members (Table 2).

We defined office hours for possible outpatient medical treatment as from Monday through Friday, 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM. Hours outside of this range were designated as “non-office hours”. The number of visitors visiting during non-office hours was 0.8 times that of visitors during regular non-office hours (RR, 0.778; 95% CI, 0.721 to 0.839; P<0.001) (Tables 3 and 4).

Patients aged >16 years were classified as adults and those <16 years were classified as pediatric patients. Overall, 35.3% of adult patients and 26.0% of pediatric patients had no visitors. Despite this, adult and pediatric patients did not have a significantly different number of visitors (RR, 0.955; 95% CI, 0.894 to 1.021; P=0.178) (Tables 3 and 4).

The means of arrival at the ED were classified into three major categories: public EMS ambulance, private EMS ambulance, or by car or on foot. Patients who arrived by car or on foot had a significantly lower number of visitors: 0.7 times that of patients who arrived by public EMS ambulance (RR, 0.701; 95% CI, 0.645 to 0.763; P≤0.001) (Tables 3 and 4).

The average time spent by a patient in the ED during the five months preceding the study period was 12.4 hours. Thus, we defined an extended stay as ≥12 hours. Patients who stayed ≥12 hours had 2.1 times more visitors than patients who stayed <12 hours (RR, 2.143; 95% CI, 1.984 to 2.315; P<0.001) (Tables 3 and 4).

We divided the disposition of patients into hospitalization to the GW, hospitalization to the ICU, discharge from the hospital, transfer, death while hospitalized, and dead on arrival and analyzed the number of visitors for each group. The number of visitors of patients discharged was 0.8 times that of the number of visitors of patients admitted to a GW (RR, 0.792; 95% CI, 0.727 to 0.863; P<0.001) (Tables 3 and 4). When we analyzed the number of visitors according to the patients’ length of stay in the ED before being admitted to the GW, the visitor-to-patient ratio tended to increase with longer lengths of stay (Table 5).

The major findings of our study were that the majority of visitors were accompanying persons, and the number of visitors per patient of those using EMS was more than that of ambulatory patients. The length of stay in the ED and ED disposition were also associated with the number of visitors per patient.

ED patients usually need some assistance from visitors. Totten et al. [10] defined the roles of visitors, especially persons accompanying patients to the ED, as providing emotional support and physical help to patients and helping bridge the gap between doctors and patients. However, despite the positive role of visitors, because they come in close contact with patients with infectious diseases, they are able to facilitate the spread of infectious diseases; this is why frequent, unlimited visits to the ED need to be controlled. Therefore, registration in a visitor’s book in the ED was an essential step in preventing the spread of infection. We will also install a security gate that will only allow entry to those with a visitor’s tag and limit distribution to one per patient. Although the Korean CDC recommended the registration of ED visitors in a guest’s book, it was not legally enforceable. If a visitor refused to register in the visitor’s book, we could not get the information we needed to control and track them. In fact, 2% of the visitors to the ED refused to register or provided incorrect information during our study. In addition, when a patient has entered the end-of-life stage, it is common for several visitors to visit the ED patient at once. There was a case where only one visitor registered as the representative of a group. It was difficult to control the visitors because of the Korean cultural background. In such cases, measures should be in place to minimize the contact between the visitors and other ED patients.

Public and private EMS ambulance staff and EMTs also accounted for a considerable proportion (26%) of all visitors. In many hospitals in Korea, when patients arrive, they are usually triaged in the inner zone of the ED. If patients are triaged outside the ED, except when a patient is in a life-threatening condition, the ambulance staff will be able to hand over the patient to the medical staff without entering the ED. After the MERS outbreak, all patients who arrived at our hospital, including those who arrived in an ambulance, should be triaged outside the ED unless they required immediate life-saving medical interventions.

The number of visitors tended to increase with increasing time spent in the ED; patients with an extended stay had twice as many visitors as patients with a shorter stay. This result is similar to that of patients admitted to the GW. As the number of visitors increases, congestion in the ED increases, and the chance of close contact with infected patients increases. Therefore, reducing the number of visitors is essential for infection control in the ED. To achieve this, in addition to the suggestions we mentioned earlier, we strictly implemented the ‘2-4-8 rule’, which was already in place in our hospital. It aims to complete a consultation within two hours, make a disposition decision within four hours, and ensure that the patient is moved to a ward bed within eight hours of registration in the ED. We were able to reduce the length of stay in the ED by holding monthly meetings to ensure that these rules were being implemented and find where improvements were needed.

In addition to controlling the number of visitors to prevent the spread of infection, the space and structure inside the ED were also improved. In EDs in Korea, the spacing between beds is very narrow (1−1.2 m), with only curtains separating the beds. Additionally, EDs have a shortage of negative-pressure isolation rooms [11]. After the MERS outbreak, we also renovated our ED to secure a bed-spacing gap of ≥1.6 m, to establish a separate zone for patients with infectious disease [12]. However, the overcrowding of the ED, one of the major factors of the MERS outbreak, worsened. The number of beds was not insufficient to accommodate the ED patients, so they widened the bed gap. It was almost impossible to keep a 1.6 m interval between the coughing patients sitting side by side in a chair [13].

This study has several limitations. First, it included only one tertiary hospital ED in Korea and the study period of 21 days was short. Second, we could not verify and secure the personal information that visitors provided. Personal information is essential for tracking visitors after they have been identified as having contact with an infected patient. In addition, a security plan should be prepared to keep personal information safe from leakage.

In conclusion, the most relevant factor in the number of visitors was the length of stay of patients in the ED. Therefore, a method for reducing the length of stay in the ED should be prepared; this should include policy changes such as an improvement of the medical delivery system and not just a structural change in the ED. Efficient control of ED visitors is also necessary. The ED is a space where anyone can receive medical treatment anytime, but it has also been recognized as a space where anyone can visit. However, EDs need to be defined as controlled areas that provide independent care for patients, and visitors should adhere to certain guidelines, such as in intensive care units. To do this, it is essential to not only support the government’s policy, but also to change the public’s awareness. In addition, the hospital itself should try to manage the nosocomial infections in the ED with an improved attitude.

Table 1.

Number of visitors per patient

Table 2.

Breakdown of visitors by purpose and their relationship with patients for each day

| Day of visit | Patient | Total |

Personal visitora) |

Non-personal visitor |

Others |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate family members | Other relatives | Acquaintances | 119 Ambulance staffb) | 129 Ambulance staffc) | 112 Police | MDC employee | |||

| 2015-07-06 | 199 | 264 | 174 | 4 | 9 | 54 | 16 | 0 | 7 |

| 2015-07-07 | 161 | 268 | 172 | 9 | 19 | 57 | 10 | 0 | 1 |

| 2015-07-08 | 165 | 240 | 148 | 3 | 6 | 54 | 24 | 2 | 3 |

| 2015-07-09 | 177 | 252 | 153 | 1 | 11 | 64 | 13 | 5 | 5 |

| 2015-07-10 | 193 | 283 | 183 | 6 | 14 | 51 | 15 | 2 | 12 |

| 2015-07-11 | 222 | 274 | 181 | 3 | 24 | 53 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| 2015-07-12 | 283 | 364 | 223 | 1 | 22 | 99 | 14 | 2 | 3 |

| 2015-07-13 | 181 | 296 | 186 | 4 | 17 | 65 | 20 | 0 | 4 |

| 2015-07-14 | 181 | 303 | 168 | 6 | 24 | 75 | 15 | 2 | 13 |

| 2015-07-15 | 164 | 294 | 163 | 16 | 14 | 74 | 20 | 0 | 7 |

| 2015-07-16 | 152 | 252 | 150 | 5 | 10 | 64 | 18 | 1 | 4 |

| 2015-07-17 | 180 | 271 | 163 | 3 | 17 | 61 | 14 | 3 | 10 |

| 2015-07-18 | 231 | 283 | 187 | 2 | 25 | 59 | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| 2015-07-19 | 282 | 267 | 172 | 4 | 18 | 63 | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| 2015-07-20 | 204 | 277 | 184 | 3 | 11 | 61 | 13 | 2 | 3 |

| 2015-07-21 | 182 | 270 | 190 | 5 | 19 | 34 | 12 | 0 | 10 |

| 2015-07-22 | 139 | 170 | 108 | 7 | 10 | 17 | 19 | 0 | 9 |

| 2015-07-23 | 164 | 185 | 132 | 3 | 15 | 27 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 2015-07-24 | 175 | 223 | 139 | 4 | 12 | 55 | 10 | 0 | 3 |

| 2015-07-25 | 219 | 185 | 143 | 0 | 13 | 20 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015-07-26 | 285 | 265 | 212 | 4 | 15 | 29 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 4,139 | 5,486 | 3,531 (64.4%) | 93 (1.7%) | 325 (5.9%) | 1,136 (20.7%) | 278 (5.1%) | 23 (0.4%) | 100 (1.9%) |

Table 3.

Comparison between the number of visitors and registered patients, according to various factors

| Variable | Visitor | Patient | Visitor per patient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day of the week | |||

| Monday | 592 | 584 | 1.01 |

| Tuesday | 612 | 524 | 1.17 |

| Wednesday | 475 | 468 | 1.01 |

| Thursday | 480 | 493 | 0.97 |

| Friday | 541 | 548 | 0.99 |

| Saturday | 578 | 672 | 0.86 |

| Sunday | 671 | 850 | 0.79 |

| Weekday | 2,700 | 2,617 | 1.03 |

| Weekend | 1,249 | 1,522 | 0.82 |

| Time of the day | |||

| Office hours | 1,195 | 998 | 1.20 |

| Non-office hours | 1505 | 1619 | 0.93 |

| Age of patient (yr) | |||

| Adult (≥16) | 2669 | 2756 | 0.97 |

| Pediatric (<16) | 1280 | 1383 | 0.93 |

| Mode of visit | |||

| 119a) | 669 | 538 | 1.24 |

| 129b) | 372 | 264 | 1.41 |

| Non-ambulance | 2,908 | 3,337 | 0.87 |

| Length of stay in the emergency department (hr) | |||

| ≥12 | 814 | 446 | 1.83 |

| <12 | 3,153 | 3,693 | 0.85 |

| Patient disposition | |||

| General ward | 621 | 538 | 1.15 |

| Intensive care unit | 131 | 109 | 1.20 |

| Discharge | 3,147 | 3,431 | 0.92 |

| Transfer | 31 | 32 | 0.97 |

| Died | 12 | 8 | 1.50 |

| Dead on arrival | 7 | 21 | 0.33 |

Table 4.

Poisson regression analysis predicting the number of visitors for a patient in the emergency department

| Variable | Value | Relative risk | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day of the week | Tuesday vs. Monday | 1.156 | 1.032–1.294 | 0.012 |

| Wednesday vs. Monday | 1.005 | 0.890–1.134 | 0.940 | |

| Thursday vs. Monday | 0.964 | 0.854–1.087 | 0.548 | |

| Friday vs. Monday | 0.977 | 0.870–1.098 | 0.698 | |

| Saturday vs. Monday | 0.851 | 0.759–0.955 | 0.006 | |

| Sunday vs. Monday | 0.781 | 0.700–0.873 | <0.001 | |

| Weekend vs. weekday | 0.796 | 0.744–0.851 | <0.001 | |

| Time of the day | Office vs. non-office hours | 0.778 | 0.721–0.839 | <0.001 |

| Age of patient | Pediatrica) vs. adult | 0.955 | 0.894–1.021 | 0.178 |

| Mode of visit | 129b) vs. 119c) | 1.104 | 0.971–1.255 | 0.130 |

| Non-ambulance vs. 119c) | 0.701 | 0.645–0.763 | <0.001 | |

| Length of stay in the emergency department | ≥12 hr vs. <12 hr | 2.143 | 1.984–2.315 | <0.001 |

| Patient disposition | ICU vs. GW | 1.039 | 0.860–1.254 | 0.693 |

| Discharge vs. GW | 0.792 | 0.727–0.863 | <0.001 | |

| Transfer vs. GW | 0.837 | 0.584–1.201 | 0.335 | |

| Expire vs. GW | 1.296 | 0.732–2.295 | 0.373 | |

| Death on arrival vs. GW | 0.288 | 0.137–0.607 | 0.001 |

REFERENCES

1. Cowling BJ, Park M, Fang VJ, Wu P, Leung GM, Wu JT. Preliminary epidemiological assessment of MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea, May to June 2015. Euro Surveill 2015;20:7–13.

2. World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Republic of Korea [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 [cited 2017 May 24]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/21-july-2015-mers-korea/en/.

3. Ki M. 2015 MERS outbreak in Korea: hospital-to-hospital transmission. Epidemiol Health 2015;37:e2015033.

4. Park GE, Ko JH, Peck KR, et al. Control of an outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in a tertiary hospital in Korea. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:87–93.

5. Lee JK. MERS Countermeasures as one of global health security agenda. J Korean Med Sci 2015;30:997–8.

6. World Health Organization. WHO statement on the ninth meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee regarding MERS-CoV [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 [cited 2017 May 24]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2015/ihr-ec-mers/en/.

7. Khan A, Farooqui A, Guan Y, Kelvin DJ. Lessons to learn from MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea. J Infect Dev Ctries 2015;9:543–6.

8. World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Fact sheet no. 401 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 [cited 2017 May 24]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/mers-cov/en/.

9. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hospital guaranteed to be safe from MERS in the country [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015 [cited 2017 May 24] Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/front_new/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=323309&page=1.

10. Totten VY, Bryant TK, Chandar AK, et al. Perspectives on visitors in the emergency department: their role and importance. J Emerg Med 2014;46:113–9.

11. Lee KH. Emergency medical services in response to the middle east respiratory syndrome outbreak in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc 2015;58:611–6.

12. Doctors News. Severance ER has been completely renovated for 0% of nosocominal infection [Internet]. Seoul: Doctors News; 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 1] Available from: http://www.doctorsnews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=118784.

13. Medipana. 4 years since 'MERS outbreak', ED overcrowding is still; The government will strengthen the medical delivery system [Internet]. Seoul: Medipana; 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 29]. Available from: http://medipana.com/news/news_viewer.asp?NewsNum=246635&MainKind=A&NewsKind=5&vCount=12&vKind=1.